Tanzanian national debt has wedged a dissonance with a rosy side trumpeted by authorities that the national debt is bearable while the antagonists claim it was a burden. This paper aims to explore the contrarian sides and will recommend economic variables that may sober the debate.

According to the data provided by Statista, Tanzania’s debt stood at $28 billion in 2018 and $38.7 billion in 2022. Tanzanian citizens place the debt at Tshs 34 Trillion.

The national debt in Tanzania was forecast to continuously increase between 2023 and 2028 by 15.7 billion U.S. dollars (+46.45 per cent). After the tenth consecutive year of increase, the national debt is estimated to reach 49.52 billion U.S. dollars and, therefore, a new peak in 2028. Notably, the national debt has continuously increased over the past years.

The indicator describes the general government gross debt, which consists of all liabilities that require payment or payments of interest and principal by the debtor to the creditor at a date or future date.

Public debt, sometimes called government debt, represents a country’s government’s total outstanding debt (bonds and other securities). It is often expressed as a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio. Public debt can be raised externally and internally, where external debt is the debt owed to lenders outside the country, and internal debt represents the government’s obligations to domestic lenders.

Public debt is an essential resource for a government to finance public spending and fill holes in the budget. Public debt as a percentage of GDP usually indicates a government’s ability to meet its future obligations.

An argument in favour of whether a national debt is bearable must be measured against the ability of the government to meet its obligations, which include the domestic budget and servicing of internal and external debts. A failure to pay up budgeted government expenditures, including servicing debts, leads that country to default, implying a failure to meet those obligations.

A debt-to-GDP ratio is often considered the best tool to assess whether a government can still pay its obligations. It is a weapon fraught with glaring flaws, but it is still considered the most efficient method to capture the solvency of any nation.

Tanzanian Public debt to GDP ratio from 2018 to 2023 is as follows: 40.5, 39.1, 39.8, and 42.1, respectively. In the same period, countries that are serial defaulters, such as Argentina, have the following ratios: 85, 89.8, 103.9, and 80.6. However, other countries with higher ratios are in Europe and have not defaulted or shown stress to default.

Such countries, such as Austria, had a ratio of 74.1, 70.6, 83.0 and 82.5 in the same period. Australia has a balance that mirrors Tanzanian ones of 41.8, 46.7, 57.2 and 55.9 during the same period under consideration. The quoted debt-to-GDP ratio statistics are available on the FocusEconomics website.

READ MORE: Africa’s Debt Crisis Report: IMF Releases List of Top Ten African Countries with the Highest Debts.

So, from the presented data, the public debt to GDP ratio is insufficient to decide whether any country is under duress to meet its obligations once that ratio is over a certain percentage. The weakness of deploying Public debt to GDP is that GDP is a measure of the central tendency of how the economy performs but may not necessarily capture the actual capacity of the government to service loans and their accompanying interest payments.

In simplistic terms, GDP is the wealth of a nation, but that criterion to evaluate the capacity of a nation to service its debt obligations is misleading. We shall explain. In developing countries such as Tanzania, most GDP is in the informal sector. Once it is in the formal sector, the capability of the government to squeeze surplus value is limited by many factors, rendering the application of the debt-to-GDP ratio to determine the country’s solvency very flawed.

For once, the informal sector is uncaptured, implying that her contribution to the national budget, where funds are allocated to service debts, is minuscule. However, the percentage of GDP attributed to the informal sector is significant. According to World Economics, Tanzania’s informal economy is estimated at 46.7%, representing approximately $82 billion at GDP PPP levels.

The contribution of the shadow or informal economy in Tanzania is almost 50% of the GDP, while their tax contribution remains unquantifiable but low. According to the Tanzanian Bureau of Statistics, domestic tax collections between 2018 and 2022 ranged from Tshs 17 Trillions to Tshs 27 Trillions, and government expenditures ranged from Tshs 20.5 Trillions to Tshs 34 Trillions.

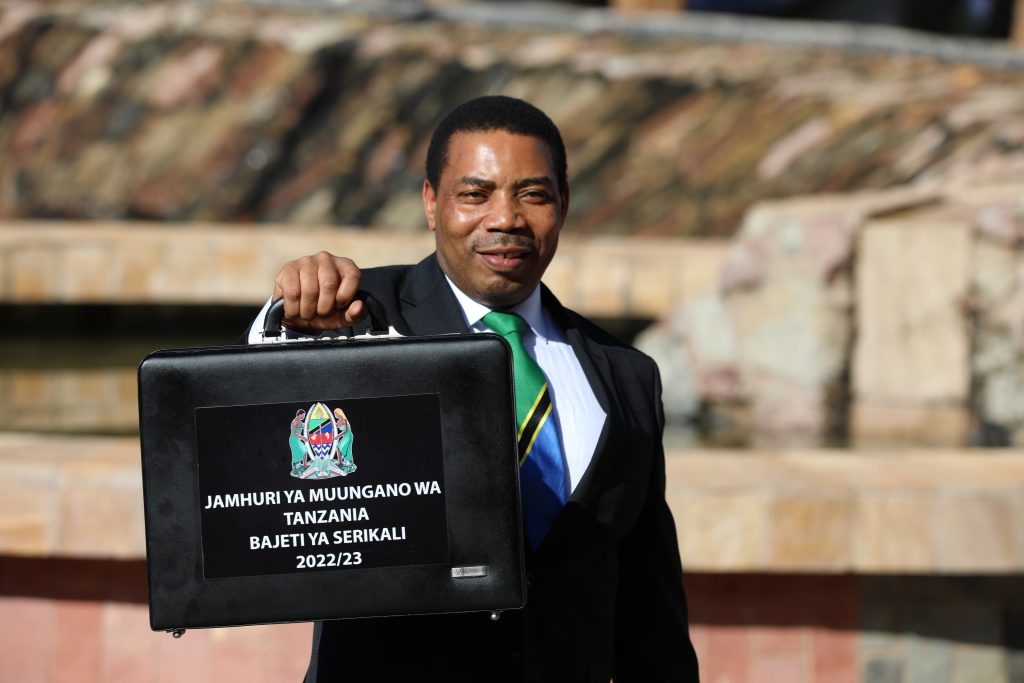

According to Trading Economics, the GDP in 2022 was $ 75.73. With 46.7% of that GDP accounted for by the informal sector, the formal sector’s contribution to the GDP was $ 31.1 Billion. Tanzania’s budget for the financial year 2022/23 is 41.48 trillion Shillings ($18 billion). The Tanzania budget combines tax revenues, domestic and external debts and grants.

The percentage of debt to the GDP in 2022 stands at 39. 8 implying that the debt was $30.14 Billion. The obligation to the GDP ratio varies depending on who prepares it. For example, Statista puts it at 42—58 in the same year of 2022. However, what is noteworthy is that such variations are not statistically significant.

The unclear issue is the interest income to meet debt obligations, knowing these loans are a mixture of long-term and short-term. According to Trading Economics, external debt in Tanzania increased to 29447.20 million USD in November from 29018.20 million USD in October 2023.

External Debt in Tanzania averaged 18774.23 USD Million from 2011 until 2023, reaching an all-time high of 30252.70 USD Million in June of 2023 and a record low of 2469.70 USD Million in December 2011. source: Bank of Tanzania

According to Tanzanian joint WB- IMF, the debt-service-to-export ratio suggested that Tanzania had limited space to absorb shocks over the medium term. Still, over a long time, Tanzania will regain some freedom to absorb shocks, and towards the end of the projection period, it will have substantial space.

Two countervailing factors qualified this assessment; on the one hand, Tanzania had and was projected to maintain healthy reserves above 5 months of imports, but on the other hand, the effect of the pandemic on the tourism sector was highly uncertain. It could continue to worsen the capacity of the country to earn foreign exchange, which then served to pay down debt. Given the relatively large fiscal needs (about 1 per cent of GDP) to fight the pandemic, the government must carefully balance its COVID-19 response with its broader development agenda to preserve debt sustainability.

According to the Citizen, in the 2022/23 financial year, the government requested the Parliament to approve a total of Tshs15.94 trillion for the ministry of finance for the fiscal year 2023/24, a total of Tshs 48 trillion would be spent on servicing the government debt.

By December 10th, 2022, the citizens noted that the national debt was Tshs 91 trillion, a monthly increase of $ 544.8 million. At the end of October, the external debt was Tshs 64 Trillion, or 75% of total debt, while domestic debt was Tshs 26.6 trillion. In proportionate terms, the external debt was critical in debt service.

The total budget for 2022/23 was Tshs 41. 48 Trillions or $ 18 Billion. The percentage of debt to a total budget was 38—43%. Roughly 40% of the government budget was allocated to servicing debt once one accommodates inflation and devaluation of the local currency. And, since debt servicing is part and parcel of the recurrent budget, it makes sense to know what proportion of the recurrent budget is set aside to service the debt.

Tanzania’s recurrent budget stood at Tshs 36.33 Trillion for the same financial year. With Tshs10.48 trillion, 28.9% of the recurrent budget was apportioned to servicing the debt.

The central bank said that Tanzania’s external debt service payments amounted to $27.8 million in August 2021, of which $18 million was spent on principal payments and the rest on repaying accumulating interest. The proportion of debt paid that cleared the principal amount was 64.75%. This indicates a determination to reduce the deficit, but because borrowing is unabated, such efforts are ineffective in debt reduction.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The application of debt to GDP ratio to determine whether the country can bear the brunt of the debt burden is misleading because it fails to differentiate GDP encompasses the shadow economy or the informal sector that contributes almost half of the GDP but does not contribute much in government taxes that are deployed to meet debt obligations.

A more realistic tool to gauge whether the national budget can bear the burden of debt is the recurrent budget. Currently, 28.9% of the recurrent budget is used to service debt. Parliament urgently needs to set a percentage limit between the recurrent budget and the maximum debt the government can borrow.

We suggest that the percentage stands at 30% of the recurrent budget. The Parliament ought to be the one that authorizes borrowing instead of approving the budget without knowing which areas and amounts would be targeted in the borrowing.

External debt, which accounts for almost three-quarters of the whole debt, was sourced to cater for transportation, social services, and others.

To directly link debt repayment obligations, future borrowing should be limited to productive sectors, and sectors like social services should be left to the internal revenue collection layout.