Tanzania is often described as blessed. It is home to the world’s only source of Tanzanite, vast reserves of natural gas, fertile soils, and the majesty of Mount Kilimanjaro. Leaders often refer to these as “God-given resources,” symbols of destiny and national pride. But blessings can also be curses.

Natural wealth can strengthen rulers without strengthening citizens. It can finance subsidies and prestige projects while silencing accountability. Or, if managed wisely, it can fund schools, hospitals, and institutions that turn subjects (wananchi) into citizens (raia).

As one reflection puts it: “Wananchi hufaidika kwa zawadi za Mungu; raia hufaidika kwa haki za nchi yao.” Subjects benefit from God’s gifts; citizens benefit from their country’s rights.

The paradox is simple but profound: resources can either entrench subjecthood or nurture citizenship. Tanzania’s challenge is to transform natural wealth from passive gifts into active rights.

The Tanzanite & Kilimanjaro Debates, Heritage as Sovereignty

Few symbols illustrate the paradox better than Tanzanite and Kilimanjaro.

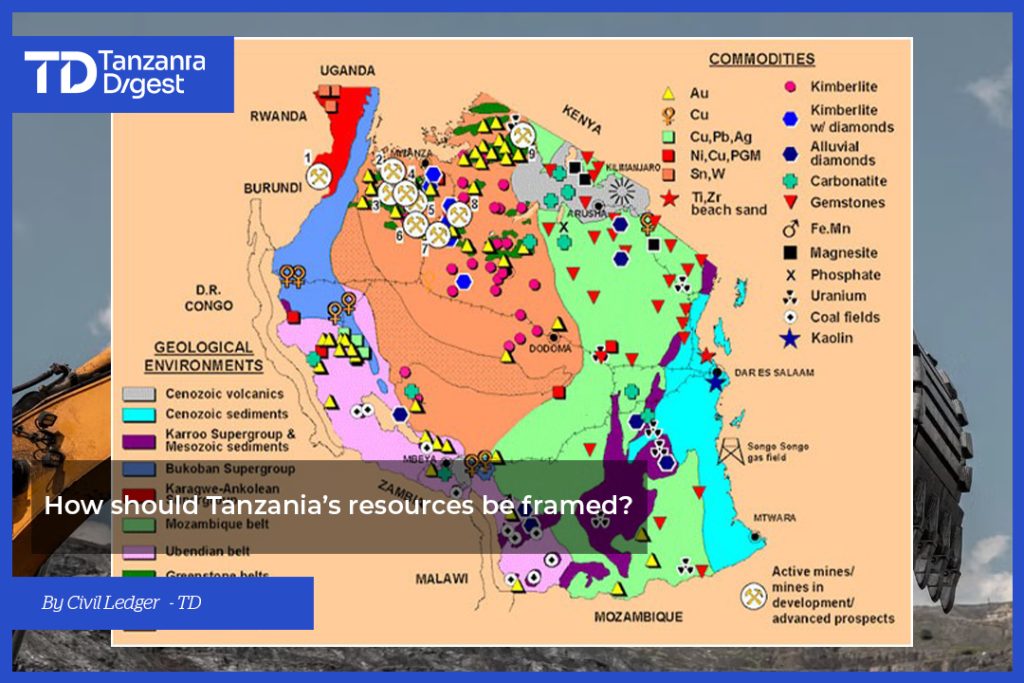

Tanzanite, found only in Tanzania, has become a symbol of national pride and national controversy. For decades, debates have raged over how much value Tanzania truly retains from its mining. Foreign companies extracted and exported much of the wealth, while local communities near Mererani often remained poor. Smuggling was rampant, revenues leaked, and citizens felt excluded from the resource that was supposed to be theirs.

The government responded with interventions, including building a perimeter wall around Tanzanite mines and tightening export controls. The message was clear: this resource belongs to the nation. Yet questions lingered. If Tanzanite is a national heritage, are citizens its rightful co-owners or merely its spectators? Does it create rights with enforceable claims, or does wananchi wait for leaders to decide their share?

Kilimanjaro tells a similar story. The mountain is a global icon, drawing climbers, tourists, and revenue from across the world. Yet debates continue about who benefits most: international tour operators or local citizens? For some, Kilimanjaro is simply a tourist attraction. For others, it is a sovereign symbol, an inheritance of all Tanzanians, not a commodity for foreign profit.

Both Tanzanite and Kilimanjaro highlight the tension between resources as heritage and resources as wealth. Heritage implies ownership by the people, rights that must be respected. Wealth, in practice, has often been controlled by elites or external actors. The gap between the symbolism of national pride and the reality of citizen benefit remains wide.

The LNG Negotiations: Citizens Left Out?

If Tanzanite and Kilimanjaro symbolize Tanzania’s heritage, the multi-billion-dollar Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) project represents the country’s future. With reserves estimated at over 57 trillion cubic feet, natural gas is projected to significantly transform the economy, potentially generating billions of dollars in revenue. The project has been in negotiation for over a decade, involving international giants such as Shell and Equinor.

But for many Tanzanians, LNG has become a story of delay, opacity, and elite negotiation. Announcements of “final agreements” have been made repeatedly, often timed to coincide with election cycles. Leaders assure wananchi that they will benefit, but the process has largely excluded the voices of ordinary people. Civil society has complained about the lack of transparency in contracts. Communities near Lindi and Mtwara, the heartlands of LNG development, often feel sidelined in decisions that will directly affect their land, environment, and livelihoods.

This gap is dangerous. When citizens are promised benefits but denied participation, they remain wananchi waiting for handouts, rather than raia asserting ownership. The rhetoric of “wananchi will benefit” is paternalistic: it suggests that citizens must wait for rulers to deliver gifts. An actual citizen economy would frame LNG not as a handout but as a right, revenue that belongs to the people, managed in trust by the state.

The LNG negotiations illustrate the broader paradox: natural wealth is celebrated as a national blessing, but often managed as an elite asset. Without transparency and participation, it risks becoming a tool for ruling over subjects, rather than leading citizens.

The Rentier Danger: Resources as Pacifiers

The risk Tanzania faces is the rentier danger, when natural resource wealth finances the state without deepening taxation, accountability, or citizenship.

Rentier states rely on rents from oil, gas, or minerals, allowing rulers to bypass their citizens. Instead of taxing people directly, they tax corporations or export revenues. This makes the state accountable upward (to investors, donors, or markets) rather than downward (to citizens). Citizens, in turn, are pacified with subsidies, handouts, or low taxes. They receive bread, but not dignity.

Africa is replete with examples. In Angola, oil revenues enriched elites while citizens endured poverty. Subsidies bought silence, but institutions rotted. In Equatorial Guinea, one of Africa’s wealthiest countries by GDP per capita, most citizens remain poor while leaders enjoy vast rents. These are nations of subjects, not citizens.

The logic is seductive for rulers. Handouts are cheaper than accountability. It is easier to pacify wananchi with subsidies than to empower raia with rights. But the long-term cost is instability. When rents decline, the silence breaks, and citizens demand the rights they were long denied.

For Tanzania, the LNG project and other resource revenues pose this risk. If wealth is managed as rents, Tanzanians will remain wananchi, beneficiaries of allowances. If wealth is managed through transparent taxation and citizen oversight, Tanzanians will become raia, co-owners of their national wealth.

The paradox of resources is global: they can be a ladder of development or a trap of dependency. The difference lies not in the minerals themselves but in the fiscal and political choices made.

Botswana is Africa’s most famous success story. At independence in 1966, it was one of the poorest countries in the world, with little infrastructure and fragile institutions. Then diamonds were discovered. Instead of collapsing into rentierism, Botswana established a governance model that treated diamonds as national wealth rather than private rents. Revenues were directed into a transparent fiscal system, funding free primary education, healthcare, and infrastructure. Importantly, taxation did not disappear; citizens continued to contribute through taxes, ensuring that the link between the state and the people remained intact. This dual system, natural wealth plus taxation, strengthened institutions and cultivated citizenship. While Botswana is not entirely free from inequality or elite dominance, its institutions are significantly stronger than those of most rentier economies. Citizens know where diamond wealth goes; they expect accountability.

Nigeria, by contrast, followed the opposite path. Oil was discovered in the 1950s, and by the 1970s, Nigeria had become one of the world’s largest oil exporters. Oil rents flooded state coffers, but instead of building institutions, they fueled patronage and corruption. Citizens paid little direct tax, so rulers had no incentive to answer to them. Subsidies were used to pacify the population, but they eroded the culture of citizenship. Institutions decayed, and the state grew more accountable to oil companies and foreign creditors than to its own people.

The contrast is not about culture, geography, or destiny; it is about political choice. Botswana deliberately built taxation and transparency into its resource governance. Nigeria abandoned taxation, relying instead on oil rents. One created raia, the other perpetuated wananchi.

For Tanzania, these examples are not abstract. They are warnings. LNG, Tanzanite, and gold can either build institutions that strengthen citizenship or rents that entrench subjecthood.

Tanzania’s Choice, Resources as Rights

Tanzania’s future hinges on a simple yet profound question: will its natural wealth be managed as a gift for its subjects or as a right for its citizens?

The language of politics today often leans toward paternalism: leaders promise that “wananchi will benefit” from resources. But such framing is dangerous. It suggests that benefits are discretionary, delivered by rulers at their convenience. It keeps citizens in a state of waiting, grateful for handouts instead of demanding their rights.

To reframe resources as citizen rights, Tanzania must make three deliberate commitments:

- Transparency as Citizenship. Contracts with foreign companies should not be considered state secrets, but rather public documents. Parliamentary debates, civil society scrutiny, and community consultations must be routine. When citizens know the terms of extraction, they see themselves as co-owners of wealth, not bystanders.

- Revenue as Obligation, Not Charity. Resource revenues must flow through sovereign wealth funds or development programs that are transparent, audited, and tied to citizen priorities. If revenues fund visible services, such as schools, clinics, and clean water, citizens recognize them as their right, not as gifts from leaders.

- Taxation Must Endure. Resource rents must never replace taxes. If citizens stop paying taxes because rents are “enough,” the culture of accountability collapses. However, if resource wealth complements taxation, citizens remain financially and politically tied to the state. Only then can resources strengthen raia rather than pacify wananchi.

Tanzania’s crossroads are clear. It can follow the rentier logic of “God’s gifts for the people,” or it can choose the republican logic of “citizens’ rights from national wealth.” The first creates dependency, the second creates democracy.

From Gifts to Rights

Natural wealth is often spoken of in divine terms, with Tanzanite referred to as “God’s jewel,” Kilimanjaro as “God’s roof,” and gas as “God’s blessing.” But democracy is not built on gifts. It is built on rights.

Resources can sustain subjects if treated as favors, or empower citizens if treated as entitlements. The choice is political, not geological.

As one reflection puts it: “Wananchi hufaidika kwa zawadi za Mungu; raia hufaidika kwa haki za nchi yao.” Subjects benefit from God’s gifts; citizens benefit from their country’s rights.

Tanzania’s resource paradox will be resolved not by how much gas or Tanzanite is mined, but by how it is framed. If citizens are treated as passive beneficiaries, the curse will endure. If they are recognized as rightful co-owners, the blessing will be democracy itself.