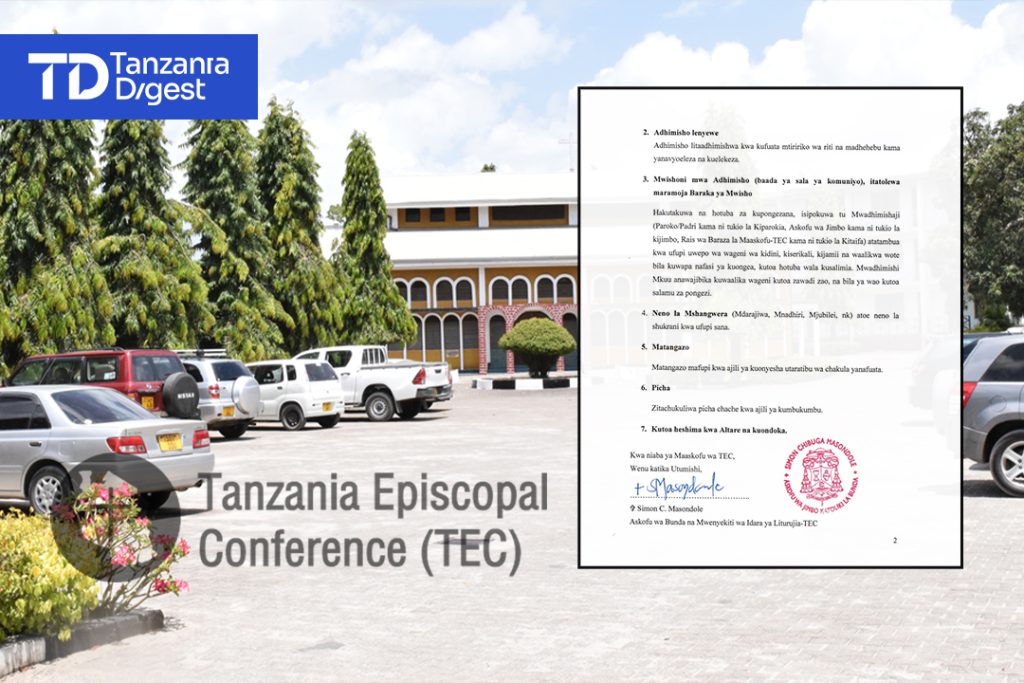

In a moment of high and tense political environment as we are heading to general elections, the Tanzania Episcopal Church has, on 16th – 19th June, 2025, issued guidelines that ban non-Roman Catholic clergy from making speeches.

The directive noted that there has been a new culture where, after the processions, individuals tend to exploit the opportunities to speak, advertise, or campaign for certain causes. Clerics may allow leaders to offer their offertory, but will no longer permit them to speak.

Clearly, the Episcopalian leadership had its eyes on political speech. This comes at a time when CCM has banned religious affiliations from engaging in political speech. The most extreme action taken by the government was the deregistration of the Bishop Gwajima ministries known as “Kanisa la Ufufuo na Uzima.”

CCM, in today’s Christian youth concert at “Tanganyika Packers Grounds,” was afforded ample time to make political speeches campaigning for the October general elections. KKKT, which organised the event, had recently received hundreds of millions of Tanzania’s shillings from the government to bankroll its project for children with special needs.

It may help to understand why CCM is livid when the churches are critical of government policies but welcome churches to advance CCM’s parochial aims.

Why did the Tanzania Episcopal leadership ban speeches from non-Roman Catholic clergy?

The Tanzania Episcopal Conference’s (TEC) ban on non-Roman Catholic clergy speeches during liturgical processions is a strategic response to escalating political tensions and government interference in religious affairs. Here’s a breakdown of the key reasons and context:

⚖️ 1. Political Repression and Church-State Tensions.

– Tanzania’s government (ruled by CCM) has systematically oppressed religious groups engaging in political criticism. In 2018, bishops denounced the suspension of opposition activities and media freedom, warning these actions “threaten national unity“.

– Authorities previously threatened to revoke church licenses for discussing politics and deregistered Bishop Gwajima’s ministry (“Kanisa la Ufufuo na Uzima“) for its outspoken stance. This creates a climate where churches face retaliation for dissent.

📅 2. Election-Year Pressure and Selective Tolerance.

– With general elections scheduled for October 2025, the political environment is agitated. Reports note rising violence, arbitrary arrests, and crackdowns on dissent.

– The government exhibits hypocrisy:

While silencing critical churches, CCM exploits compliant religious platforms. For example, at a K.K.K.T organised youth concert, CCM officials campaigned freely after K.K.K.T received “hundreds of millions” in government funding. TEC’s guidelines reject this co-option due to compromised integrity.

⛪ 3. Safeguarding Liturgical Integrity.

– TEC’s directive explicitly targets the “new culture” of post-procession speeches being used for political advertising or campaigns. By restricting non-Catholic clergy speeches, TEC aims to:

– Prevent Exploitation:

Stop political actors from hijacking religious events for propaganda.

– Maintain Neutrality:

Avoid perceptions of partisanship, especially amid government surveillance of religious services.

– Uphold Theological Focus:

Limit rituals to offertory contributions without permitting secular speeches.

🚨 4. Security and Institutional Self-Preservation.

– The April 2025 brutal attack on “Fr. Charles Kitima” (TEC Secretary General) highlighted risks to clergy critical of the government. No perpetrators have been apprehended, signalling impunity for anti-church violence.

– By banning external speeches, TEC reduces opportunities for government agents or provocateurs to instigate conflicts during Catholic events, protecting both congregants and clergy.

✋ 5. Asserting Ecclesiastical Authority.

– The guidelines reinforce that only the presiding Catholic official may “briefly acknowledge” guests without allowing speeches. This centralises control within TEC, preventing manipulation by external actors.

– It also distances TEC from government-favoured interfaith initiatives, like those of KKKT, which risk compromising the Church’s independent moral voice.

💎 Conclusion.

TEC’s ban is a defensive measure against the political weaponisation of worship spaces, reflecting broader struggles for religious autonomy under an increasingly authoritarian regime.

By curtailing non-Catholic speeches, the bishops prioritise liturgical purity, congregational safety, and institutional sovereignty amid government pressure to silence dissent. This aligns with their 2018 call to resist tactics that “destroy peace and national unity“.

Is this ban similar to the Kenyan churches on political speeches during liturgical processions?

The ban on speeches during liturgical processions issued by the Tanzania Episcopal Conference (TEC) shares “core similarities” with earlier restrictions imposed by Kenyan churches on political speeches during worship services, but also exhibits “critical differences” in scope, context, and motivation. Here’s a comparative analysis:

🔄 1. Core Similarities:

Protecting Liturgical Sanctity.

– Ban on External Speakers:

Both Tanzania’s TEC and Kenyan denominations (Anglican, Catholic, Presbyterian) prohibit non-clergy or external figures from making speeches during religious services. TEC bans non-Catholic clergy from speaking during liturgical processions, while Kenyan churches bar politicians from using pulpits for campaigns.

– Preventing Politicisation:

Both explicitly aim to stop worship spaces from becoming platforms for political campaigning. TEC cites concerns about individuals “exploiting opportunities to campaign“, mirroring Kenya’s fears that services could become “campaign rallies”.

– Structural Enforcement:

Both limit acknowledgements to brief recognition without speeches. Kenyan Archbishop Ole Sapit permits politicians to “stand and wave” but not address congregations inside sanctuaries, aligning with TEC’s allowance for offertory contributions but no speeches.

⚖️ 2. Key Differences: Scope and Targets.

– Targeted Groups:

– Tanzania:

Focuses on “non-Catholic clergy” (e.g., interfaith leaders), explicitly excluding them from speaking roles during Catholic ceremonies.

– Kenya:

Targets “politicians” across parties, regardless of religious affiliation.

– Government Pressure:

– “Tanzania’s ban coincides with state crackdowns” on critical religious figures. The deregistration of Bishop Gwajima’s church for “sermons with political overtones” and the attack on TEC Secretary-General Fr. Charles Kitima suggest the ban may be a “defensive measure against state retaliation”.

– “Kenya’s bans are church-led initiatives”, responding to public concern about corruption and electoral violence rather than direct government pressure.

🌍 3. Contextual Drivers: Political Environment.

– Tanzania’s Authoritarian Climate:

– The ban follows President Samia Suluhu Hassan’s warning against using religion for politics and the CCM government’s punitive actions against critical clergy. TEC’s move appears partly “motivated by self-preservation” amid escalating state intimidation.

– Kenya’s Electoral Violence Prevention:

– Kenyan churches framed their bans as safeguards against hate speech and ethnic conflict, referencing the 2007–08 post-election violence, where churches were attacked. The goal was to position churches as “honest arbitrators“, not to appease the state.

🏛️ 4. Broader Church-State Dynamics.

– Tanzania:

– The TEC ban reveals a **tense church-state standoff**. While CCM exploits compliant churches (e.g., funding KKKT events where it campaigned ), it silences critical voices like Gwajima. TEC’s restrictions may aim to avoid state accusations of “political interference.”

– Kenya:

– Bans reflect “church autonomy” in confronting state corruption. Archbishop Ole Sapit’s prohibition of publicised political donations challenged systemic bribery, showing churches asserting moral authority over politicians.

💎 Conclusion: Parallels with Divergent Motivations.

| No. | Aspect. | Tanzania. | Kenya. |

| 1.0 | Primary Target. | Non-Catholic clergy. | Politicians. |

| 2.0 | State Pressure. | High (crackdowns, deregistrations). | Low (church-led initiative). |

| 3.0 | Core Motivation. | Avoid state retaliation; protect liturgy. | Prevent electoral violence; curb corruption. |

| 4.0 | Relationship with the State. | Adversarial. | Corrective (churches as watchdogs). |

While both countries seek to “shield worship from politicization”, Tanzania’s ban is more reactive to state coercion, whereas Kenya’s is a proactive stance for “ethical governance”. The TEC guidelines thus reflect a uniquely Tanzanian struggle for religious integrity under political duress.

Read more analysis by Rutashubanyuma Nestory