The privatisation policies were designed to transform the private sector, trimming the government from poorly performing companies and seal holes that were siphoning public funds to resuscitate companies on death row.

Nobody expected that the main beneficiary of the site of Tanganyika Packers would have been politicians who would sell it to the Evangelicals. We had expected whoever would have bought the meat processing plant would have stringent conditionality to ensure he would never abandon the primary objectives of the company.

However, once the company was sold to well-connected politicians, the narratives quickly shifted from industrial production to real estate. The argument became: we sold it, and we could no longer dictate what the buyer did with it! It was a complete sellout of the founding father’s aspirations of creating an industrial base.

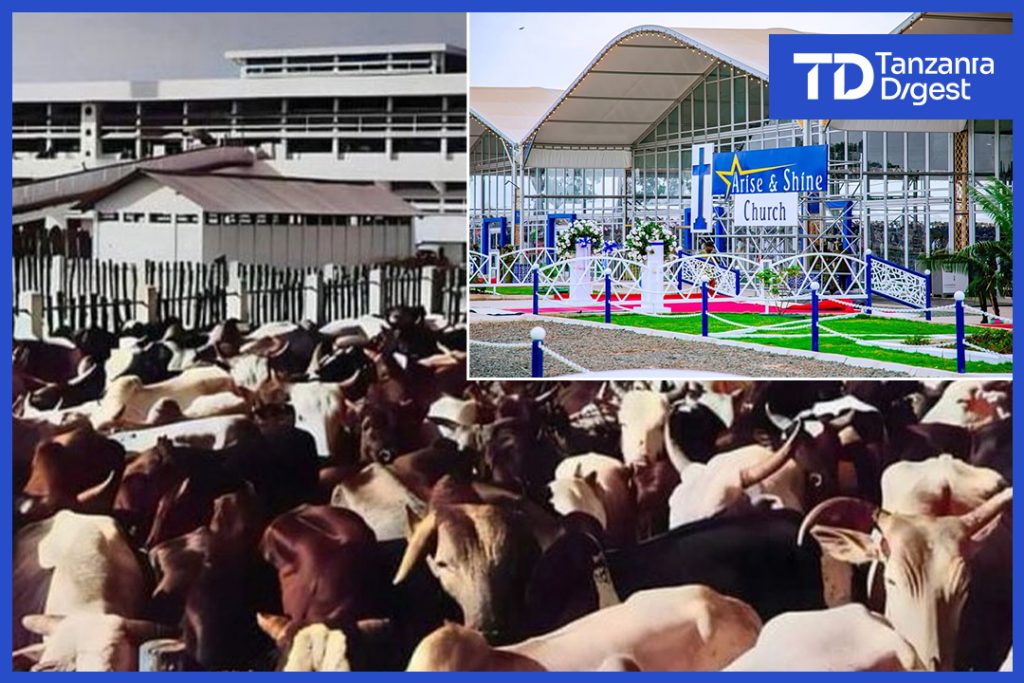

The conversion of the former Tanganyika Packers Limited (TPL) site in Kawe, Dar es Salaam, into the “Arise & Shine Church” led by Boniface Mwamposa has sparked public debate, reflecting tensions between historical preservation, industrial legacy, and contemporary land use. Here’s a synthesis of key issues based on available information:

1. Historical Significance of Tanganyika Packers.

– Colonial Origins:

Established in 1947 by the UK-based Liebig’s Extract of Meat Corporation (LEMCO), TPL was Tanzania’s sole export-oriented slaughterhouse and beef-canning factory. It employed 1,200–2,500 workers and anchored a working-class community.

– Economic Role:

It processed beef for export to Europe (especially the UK), military rations, and by-products like canned meat, hides, bone meal, and animal fat for soap. The name “Kawe” derives from “Cows Way,” reflecting its role in cattle transportation from Pugu Station to the factory.

– Decline:

Nationalized in 1974 under state socialism, TPL lost its international marketing license and shifted to domestic supply. Drought, disease, and mismanagement crippled operations, leading to closure in 1993.

2. Controversy Over Land Conversion.

– Site Deterioration:

The 263-acre Kawe site is now dilapidated, with machinery missing and structures collapsing. Residents question the fate of assets and allege land grabs by politicians and religious leaders.

– Church Inauguration:

The government-backed launch of “Arise & Shine Church” has drawn criticism. Critics argue:

– The land could better serve public needs (e.g., hospitals, schools, government offices to decongest Dar es Salaam).

– Industrial revival (e.g., meat processing or food factories) would align with Tanzania’s agricultural potential.

– Ownership Disputes:

Part of the land was sold to businessman Adamjee (former Kawe MP), but development stalled. Other segments are reportedly controlled by elites, including a beachside club.

3. Systemic Failures & Public Sentiment.

– Missed Opportunities:

Tanzania, with Africa’s third-largest cattle population, failed to leverage TPL due to:

– Post-nationalization loss of global markets.

– Corruption, disease management failures, and resistance from pastoralists during the 1970s villagization policy.

– Community Frustration:

Locals lament the factory’s decay as symbolic of broader industrial neglect. They demand transparency in land reallocation and prioritize job-creating projects over religious institutions.

Conclusion.

The TPL site’s transformation into a church epitomizes unresolved tensions between Tanzania’s industrial heritage and contemporary development priorities. While repurposing unused land is pragmatic, the lack of inclusive planning and opaque deals fuels public distrust. Reviving agro-processing on this scale—potentially relocated to cattle-rich areas like Singida or Ruvu—could better honor TPL’s legacy and economic potential.

4. CCM FAILED PROMISES OF TRANSFORMATION THROUGH PRIVATISATION OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR.

The transformation of Tanganyika Packers Limited (TPL) from a colonial-era industrial powerhouse to the site of the “Arise & Shine Church” epitomizes the systemic failures of CCM’s privatization policies. This outcome starkly contrasts with Tanzania’s founding industrial aspirations and reveals how political elites subverted economic revitalization goals. Here’s a critical analysis:

⚙️ 1. Industrial Legacy vs. Privatization Betrayal.

– Historic Significance:

TPL was established in 1945 as Tanzania’s primary meat-processing complex, employing 2,500 workers and supplying canned beef to Europe. It anchored a supply chain from cattle ranches in Mloganzila to processing at Kawe, symbolizing colonial-era industrial integration.

– Privatization Promise:

Post-1990s, CCM’s privatization drive aimed to “resuscitate dying companies” by offloading loss-making state assets. TPL, closed since 1993 due to mismanagement and debt, was slated for revival under stringent industrial “conditionalities.”

– Reality:

The site was acquired by politically connected figures (including a former Kawe MP) who abandoned production to pursue lucrative real estate. The shift to non-industrial use violated the core objective of privatization: economic reactivation.

💰 2. Elite Capture and Institutional Complicity.

– Asset Stripping:

Buyers dismantled machinery for scrap metal and repurposed the 263-acre prime land for commercial ventures. One section became a beach club; another was sold to evangelical leader Boniface Mwamposa for church construction.

– State Abdication:

Officials defended this by claiming, “We sold it, so we can’t dictate usage.” This ignores:

– Tax Evasion:

Buyers exploited tax holidays meant for industrial investors.

– Land Speculation:

Politicians flipped the land at inflated prices instead of creating jobs.

– No Clawbacks:

Contracts lacked penalties for breaching revival commitments.

⛪ 3. Symbolic Insult: Church as Industrial Tombstone.

The 2025 inauguration of “Arise & Shine Church” on TPL’s ruins underscores the policy’s perversion:

– Economic Irony:

Tanzania imports $300M/year in processed meat despite having Africa’s third-largest cattle herd—a direct consequence of deindustrialization.

– Public Outrage:

Locals condemn the site as a “monument to failed promises.” As one Kawe resident lamented: “We needed hospitals or factories, not a church benefiting elites“.

📉 4. Systemic Policy Flaws.

– Corruption Enabler:

TPL’s fate mirrors broader corruption patterns. Transparency International’s 1998 index ranked Tanzania among Africa’s most corrupt nations, with elites using privatization to launder illicit wealth management.

– Ideological Hypocrisy:

CCM’s Ujamaa rhetoric championed self-reliance, yet privatization transferred national assets to private cartels. The Warioba Report (1996) exposed how privatization became a “legalized looting spree“.

🔄 5. Alternative Paths Ignored.

TPL could have been revived through:

– Agro-Industrial Zones:

Integrating with cattle corridors in Singida/Ruvu.

– Public-Private Models:

As proposed for Tanga’s port upgrades.

– Cooperative Revival:

Leveraging pastoralist networks for raw material supply .

💎 Conclusion: Mocking the Founding Vision.

The church rising from TPL’s ashes is not just a policy failure—it is a “deliberate erasure” of Julius Nyerere’s industrialization vision. CCM’s privatization, designed to “trim government,” instead trimmed national sovereignty.

Until Tanzania audits all privatized assets and enforces industrial covenants, its industrial base will remain a graveyard of elite avarice. As one mechanic in “African Motors” poignantly noted: “We fix imported cars but can’t fix a local broken system“.

Read more analysis by Rutashubanyuma Nestory

TPL is not alone, the list of ‘failed privatisation’ is quite long. However, we should bear in mind that in the vast of cases there was nothing to privatise, except loads of scrap metal- Urafiki, ZZK, Sunguratex, Morogoro Polyster Mill, Morogoro Shoes, Taboratex, Genera Tyres, Mufindi Paper Mills, Mbeyatex, Mwatex, Kiwira Coal Mines, Mang’ula Mechanical Tools,ZZK, TPL- Shinyanga, etc.

Whereas the PPSRC (Presidential Public Sector Reform Commission) became a godsend to greedy ‘compatriots’ who saw opportunity to extract bribes in order to give away what was on offer. Again, it is obvious there was no clear idea of what we aim to achieve, the roadmap to get there and how to get there. Although the law specified final decisions to sell/ partnership/ reform to be approved by cabinet, this institution, headed by the Head of State, appears to have abdicated its legal responsibility, leaving vultures to rule supreme.