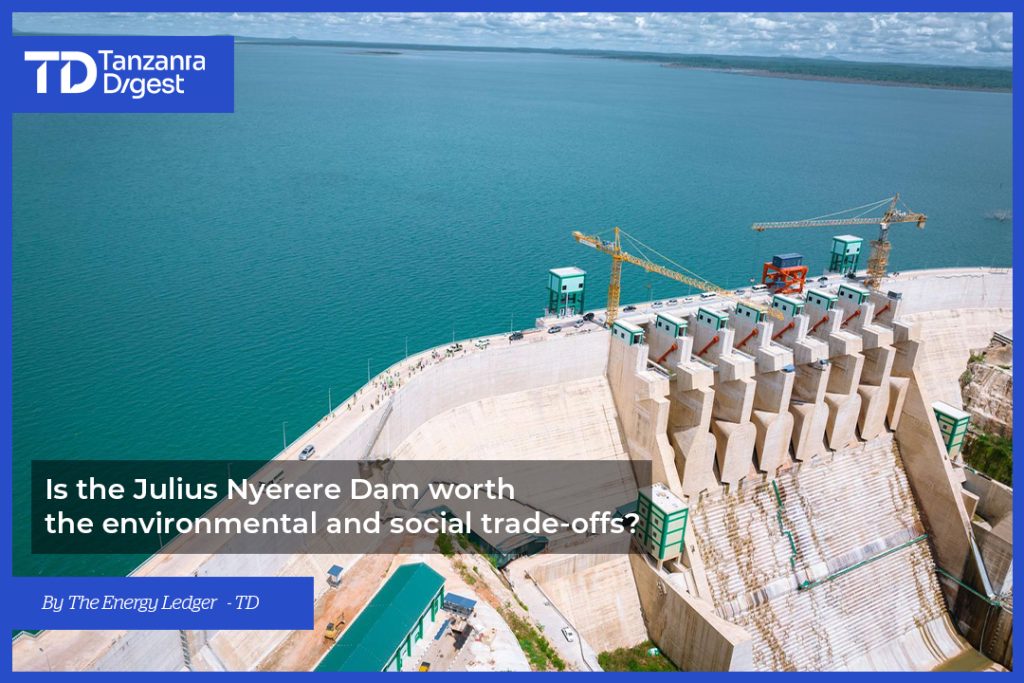

At first light on the Rufiji River, the sight is impressive. The surface is calm, but behind the dam’s walls, billions of cubic meters of water wait to be released through nine turbines. The Julius Nyerere Hydropower Plant (JNHP) now hums with the sound of national ambition, a project designed to double Tanzania’s generation capacity and mark a new era of industrial growth.

But ambition has another face. The reservoir, stretching over 1,350 square kilometers, lies inside the Selous Game Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site that has long been one of East Africa’s great ecological treasures. The Rufiji’s seasonal floods have for centuries fed downstream wetlands, mangroves, and fisheries, sustaining both biodiversity and livelihoods.

The central question is no longer whether JNHP will generate electricity; that is already happening. The question is whether Tanzania can reap the benefits of this new power without causing irreversible damage to the environmental and social systems that have sustained communities and economies for generations.

The Geography of Impact

The Selous Game Reserve, now partly reclassified as Nyerere National Park, covers approximately 50,000 km². It is home to elephants, lions, black rhinos, and vast tracts of miombo woodland. Within this protected landscape, the JNHP reservoir has flooded an area equivalent to 2–3% of the reserve, about 1,350 km².

The Rufiji River, which feeds the dam, is more than just a scenic waterway. It is the lifeline of the Rufiji Delta, a Ramsar-listed wetland complex that supports mangrove forests, inland fisheries, and coastal agriculture. These ecosystems are not merely ecological assets; they are economic ones, providing food, raw materials, and tourism value.

By regulating the river’s flow, JNHP changes more than water levels. It alters the pulse of an entire system: the timing and intensity of floods, the replenishment of soils, and the migration patterns of both fish and wildlife. The area of impact stretches far beyond the footprint of the dam itself.

Environmental Costs

The hydrological changes are the most immediate and predictable. For centuries, the Rufiji’s wet-season floods have recharged floodplain agriculture, replenished inland lakes, and delivered sediment to the mangroves. With the dam in place, these pulses will be moderated useful for power generation stability, but potentially harmful for ecosystems that depend on seasonal extremes.

Biodiversity is also at risk. The inundation has fragmented habitats and submerged breeding grounds for terrestrial and aquatic species. Wildlife corridors that once connected different parts of the reserve are now interrupted by deep water. While some species may adapt, others could see population declines, especially in the absence of targeted conservation measures.

There is also an international dimension. UNESCO and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) have expressed concerns that the project’s Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) was inadequate to evaluate the full spectrum of risks. If left unmanaged, these impacts could threaten Selous’s status as a World Heritage site. This loss would harm Tanzania’s reputation in global conservation circles and potentially decrease tourism revenue from one of its most renowned reserves.

Finally, the reduced sediment flow downstream could weaken the Rufiji Delta’s mangroves. These mangroves act as nurseries for fish, protect coastal communities from storm surges, and store significant amounts of carbon. Their decline would have cascading economic and environmental consequences, from reduced fisheries output to higher vulnerability to climate-related disasters.

Social Impacts

Beyond the ecological boundaries of the Selous, the Rufiji River sustains human life in ways that are less visible on engineering schematics but equally vital. Communities along the river depend on flood-recession agriculture, planting crops in nutrient-rich soils left behind when the seasonal waters recede. These cycles have provided reliable harvests for generations without the need for costly inputs.

The dam’s regulation of water flow risks breaking that cycle. Without regular floods, soils lose fertility, crop yields drop, and farmers may be forced into more expensive or less sustainable agricultural methods.

Fishing communities face a similar challenge. The Rufiji’s seasonal flooding triggers fish migrations and breeding cycles. Reduced or altered flows can disrupt these patterns, leading to lower catches and threatening livelihoods dependent on artisanal fishing.

Social research conducted in the area reveals a troubling perception gap. While over 90% of residents are aware of the dam’s construction, 90.6% reported having no meaningful involvement in the planning process. Among those downstream, 76% believe the dam will cause more harm than benefit to their communities. This absence of early and genuine participation risks creating a legacy of alienation, a costly social deficit that could undermine the project’s long-term acceptance.

Resettlement, though less extensive than in some other mega-dam projects, still presents risks. Past Tanzanian infrastructure projects have shown that compensation schemes, if not rigorously designed and monitored, often fail to restore livelihoods, leaving displaced people poorer than before.

The Economic Equation

From a macroeconomic perspective, JNHP’s environmental and social trade-offs must be weighed against its economic benefits.

Tourism Risk:

Selous/Nyerere is one of Tanzania’s most valuable wildlife tourism destinations, attracting high-spending visitors. Any ecological degradation that leads to a downgrade or loss of UNESCO World Heritage status could directly affect visitor numbers, reducing foreign exchange earnings.

Ecosystem Services:

Wetlands, mangroves, and healthy fisheries are economic assets. The Rufiji Delta’s mangroves protect coastlines from erosion, support fisheries worth millions annually, and act as a carbon sink, a service increasingly valuable in global climate markets. Damage to these systems represents a real economic loss, even if it does not immediately appear in GDP figures.

Net Balance:

The hydropower output from JNHP could drive industrial expansion, lower power costs, and create new export opportunities in the regional electricity market. But if these gains come at the expense of long-term tourism decline, reduced fishery productivity, and degraded farmland, the net benefit may be far smaller than anticipated. The challenge for policymakers is to maximize the power benefits while actively protecting the other sectors that depend on the Rufiji system.

Mitigation and Policy Responses

If JNHP is to fulfill its promise without triggering lasting ecological or social harm, mitigation cannot be an afterthought; it must be embedded in operations from the start.

Environmental Flow Management:

Release schedules should mimic natural flood pulses to sustain downstream ecosystems and support agriculture. This necessitates incorporating ecological science into dam operations, rather than focusing solely on engineering targets for electricity generation.

Biodiversity Monitoring:

Independent ecological audits, published annually, can track the dam’s impact on wildlife, vegetation, and fisheries. These audits should be linked to adaptive management, allowing operational changes when negative trends appear.

Community Benefit-Sharing:

A fixed percentage of JNHP’s revenues could be directed into a Rufiji Development Fund to finance local infrastructure, education, and livelihood diversification projects. This would help offset disruptions and create visible, shared gains.

Climate Adaptation Planning:

Hydropower is inherently susceptible to drought cycles. Diversifying the energy mix and implementing cross-sector contingency plans will help mitigate water scarcity risks and safeguard both the power system and downstream users.

Governance and Accountability

Mega-projects succeed or fail in the long term based not only on engineering quality but on the strength of their governance systems. For JNHP, this means building institutional safeguards that ensure environmental and social commitments are not just promises in the planning documents but realities on the ground.

Inter-Ministerial Coordination:

The ministries responsible for energy, environment, tourism, and agriculture must operate in sync. Energy policy cannot be executed in isolation from conservation or community development strategies.

Transparent Reporting:

Annual reports should detail JNHP’s environmental, social, and economic performance, covering everything from power output and revenue to biodiversity trends and resettlement outcomes. Public disclosure builds trust and allows for independent scrutiny.

Stakeholder Engagement:

Community input must transition from token consultation to ongoing dialogue. A structured feedback mechanism, possibly through local development committees, can help identify issues early and support adaptive management.

Enforcement Capacity:

Regulatory bodies must have both the authority and resources to enforce compliance with environmental and social safeguards. Without this, even the most well-designed policies risk becoming unenforced guidelines.

A Shared Responsibility

The Julius Nyerere Hydropower Plant stands as a monumental investment in Tanzania’s future — a structure of concrete and steel designed to power growth for decades. Yet, its foundations are not only physical; they are equally rooted in the living systems of the Rufiji River and the communities that depend on it.

The success of JNHP will not be measured solely in megawatts produced or shillings saved on imported diesel. It will be judged by whether Tanzania can sustain the Selous’ biodiversity, preserve the Rufiji Delta’s productivity, and maintain the trust and prosperity of the communities along its banks.

This is why JNHP’s story is a shared responsibility. Energy engineers, environmental scientists, community leaders, and policymakers must all play their part. The challenge is not to choose between power and preservation but to commit to both with equal seriousness and sustained investment.

If that commitment holds, JNHP could become more than just an energy milestone. It could serve as the model for how Tanzania shapes its future: ambitious in scope, rooted in science, inclusive in governance, and balanced in the way it draws from and gives back to the land and people it serves.