Once thought to be primarily a marine problem, new research indicates that plastic pollution poses a serious threat to all living creatures. For those who need to breathe air to survive, the risks are even greater. From microplastics to nanoplastics, the dangers to humanity cannot and should not be underestimated. This article reviews the knowledge gained so far on the impacts of plastics on humanity and recommends viable solutions.

Recent scientific advances are enabling researchers to explore how micro- and nanoplastics form a critical part of the plastic pollution problem. Scientists have discovered that micro- and nanoplastics exist in every environmental compartment — from freshwater to soil and air — and in thousands of species, including humans. However, like climate change and hazardous chemicals, most plastics are invisible to the naked eye, meaning their impact often goes unnoticed.

While the sea was once depicted as the ultimate dumping ground for microplastics, these tiny particles can travel long distances and cover urban, rural, and remote areas. In fact, their ability to travel through the atmosphere allows them to move more freely and rapidly compared to those that end up in bodies of water.

The potential for long-range transport means that micro- and nanoplastics can affect locations and populations far from the sources of plastic pollution, making them “one of the most ubiquitous pollutants released by human activities” and a significant public health concern. While health impacts are still being investigated, the production and use of plastic materials are undisputedly the causes.

The Problem Diagnozed

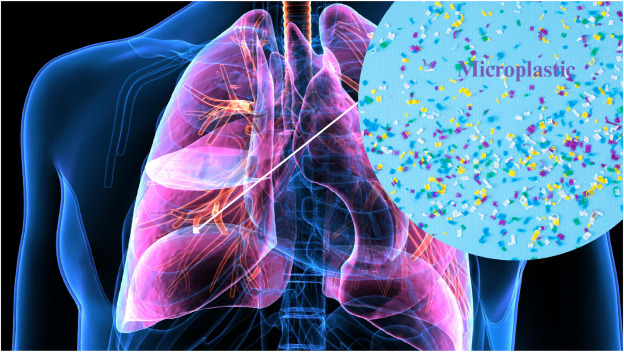

Selective investigations have found that microplastics are everywhere in human lungs. These microplastics are invisible to the human eye, making them imperceptible and not perceived as a pressing health issue. These elusive particles are inhaled, passing through the mouth and nostrils before settling at the bottom of the lungs.

Read Related: The Hidden Risks of Bottled Water: Your Health is in Uncertainty, Beyond Control

Scientists have determined that inhalation is a major contributor to human intake of micro- and nanoplastics. Exposure rates — the amount of atmospheric micro- and nanoplastics in an individual’s vicinity — can be as high as 5,700 microplastics per cubic meter. It’s estimated that humans can inhale up to 22 million micro- and nanoplastics annually.

Human activities are major contributors to atmospheric microplastics. Primary microplastics are intentionally produced at microscale for specific uses, such as in agrochemicals or pharmaceuticals. Secondary microplastics result from the mechanical, chemical, and physical fragmentation of larger plastics, including legacy plastics disposed of decades ago.

Every stage of the plastics life cycle — from extraction to production, transport, use, disposal, and remediation — emits both primary and secondary microplastics and other hazardous substances.

The spread and effects of airborne microplastics can remain localized or extend far beyond the point of release. While concentration levels vary, no location remains untouched. Airborne microplastics have been collected worldwide, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, including in France, Iran, China, Japan, Vietnam, Nepal, the United States, Colombia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Kuwait, Greece, Romania, Pakistan, and India.

Exposure to airborne microplastics can occur through inhalation, penetration through skin pores, and ingestion of contaminated food. Microplastics’ reach inside the human body depends on their properties, size, shape, and an individual’s metabolism, susceptibility, and lung anatomy.

They can enter the respiratory system through the nose or mouth, depositing in the upper airways or deep in the lungs. Evidence shows that micro- and nanoplastics can transfer from the lung epithelial surface to lung tissue, potentially reaching internal organs and the vascular system.

Microplastics can act as vectors for pathogens and toxins in the human body. Their large specific surface areas and hydrophobic nature make airborne microplastics a “Trojan Horse,” capable of hiding and carrying harmful substances inside the animals or humans who inhale, absorb, and ingest them. Therefore, understanding what’s inside plastic is as important as knowing what lies in it.

Health Impacts

Preliminary studies on the inhalation of micro- and nanoparticles of plastics show a series of adverse effects along the respiratory tract and beyond, ranging from irritation to the onset of cancer in cases of chronic exposure.

Also, read: Plastics as Edible Proteins: Can Plastic Waste Become Our Next Food Source?

These adverse effects include immediate asthma-like reactions, inflammatory reactions and fibrotic changes similar to chronic bronchitis, lung disorders such as extrinsic allergic alveolitis and chronic pneumonia, pulmonary emphysema, the development of interstitial lung diseases resulting in coughing, difficulty breathing, and reduction in lung capacity, oxidative stress and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can damage cells (cytotoxic effects), and autoimmune diseases.

Exposure to airborne microplastics does not occur in isolation. Humans are exposed to multiple pollutants and hazardous chemicals daily, including microplastics ingested via other sources such as food or drink. While research on airborne microplastics is still in its infancy, it is clear that microplastic exposure typically happens alongside other toxic substances.

These findings underscore the need for further research and the development of strategies to mitigate the risks associated with inhaling microplastics and other pollutants.

Recommendations

Unless we act now, the volume of airborne microplastic emissions will follow the expected rise in plastic production, resulting in a greater risk of spreading potentially toxic chemicals. Regulators need to dramatically reduce the production of plastics and phase out hazardous chemicals.

Humans are exposed to multiple pollutants and hazardous chemical compounds daily, including endocrine disruptors and POPs linked to diabetes, infertility, and hormone-related cancers. Drafted policies should ensure access to information on the petrochemical compounds in plastic products and processes (both voluntary and non-intentionally added) for all plastic products, not just food-grade plastics.

Banning intentionally added microplastics is the initial step. Mandatory regulations are needed to reduce the production and release of plastic and its associated compounds, thereby reducing human exposure to plastics, microplastics, and nanoplastics. Airborne micro- and nanoplastics pose significant health threats, so addressing them directly is crucial.

A systematic effort is required, beginning with the extraction of fossil fuels and associated chemicals used in plastic production. Decision-makers should support global action and strict enforcement measures in the upcoming international legally binding agreement on plastic.