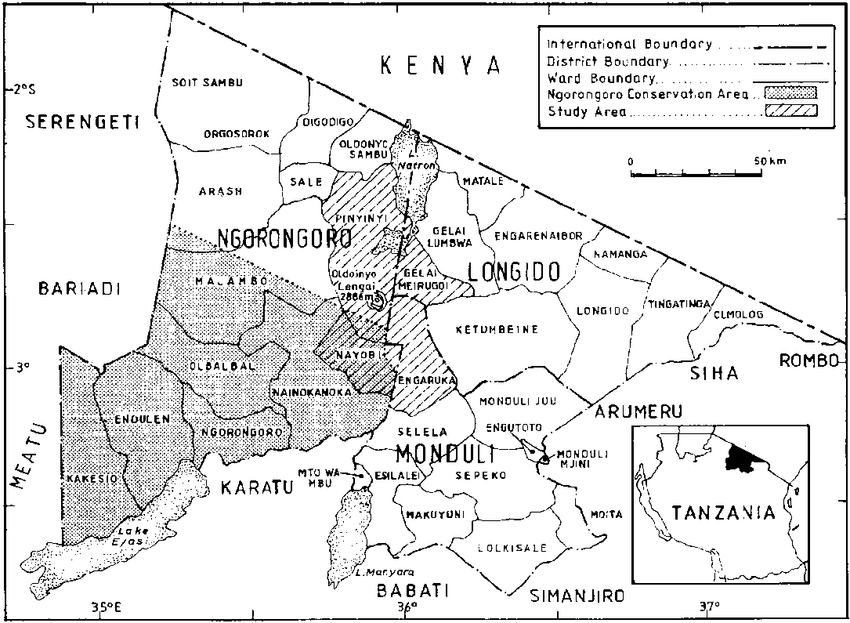

Many people when bombarded with news from Ngorongoro consider that it is the same homogenous area while it is not. Whereof, the district is one but the fates of her Wards are different. Ngorongoro District has three divisions, namely, Ngorongoro, Sale and Loliondo. This article differentiates two areas of Ngorongoro, the former and the latter two, offering an insight into their challenges and opportunities while recommending viable solutions for both.

One District, Two Facets!

The narratives of Ngorongoro will be doing an injustice to the area unless the two regions are differentiated and their problems analyzed and resolved. A clearer assessment of the three divisions within the Ngorongoro district reveals Sale, Loliondo, and Ngorongoro.

The first two have the least problems, except for the leasing of the Loliondo game reserve to a Dubai company, which is beyond the scope of this discourse. As the name suggests, the majority in Sonjo are from the Sonjo tribe, whose tribal wars with the Maasai (Maa) are legendary. The Sonjos are skilled with poison-laced arrows, making them formidable in conflict.

The Sonjos combine cultivation and livestock rearing to make a living. Unlike the Maa, the Sonjos prefer a sedentary lifestyle. Some argue that a sedentary life motivates communities to conserve their lands, unlike the pastoralist Maasai, who can move from place to place.

However, land conservation is complex. Some studies suggest that pastoralism is an advanced form of landfallowing. Grazing is limited by the availability of grasses, watersheds, and the need to avoid cattle rustlers. Both sedentary and pastoral lifestyles offer incentives to conserve natural resources for future use.

Sale and Loliondo are less restricted in land use than Ngorongoro Ward, also known as the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, where cultivation, forest harvesting, and mineral extraction are illegal. Notably, 59% of the Ngorongoro District is occupied by the Ngorongoro Ward, spanning 8,292 square kilometres.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area Dissected

Sometime in 1956, a British colonial Maasai District officer called Edward Grant was tasked with preparing a policy on how the area would be managed after it became clear that the harmonization of human activities and wildlife was seen as heading to a clash. As a result of his findings, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area was annexed in 1959 from the Serengeti National Park and became an independent management authority for the area and the people living there.

But what is least discussed and appreciated is that the influx of Maasai from the Moru Mountains in Kenya to the Serengeti plains contributed to the growth of the populations in the Serengeti plains. British Colonial settlers were expropriating Maa lands in Kenya, pushing them to the wildlife areas of the Serengeti plains.

According to the Grant report,1956, two-thirds of Maa who migrated into the Serengeti National Park were Kenyan citizens, and since it was Britain that had created the illegal immigration influx took the onus of settling them into the Ngorongoro District within Tanganyika.

The total estimate of Maa in the Serengeti plains was 9,000 in 1956 but their population grew to 48, 000 by 2005. The British colonial rule knew that settling the Maa in the Ngorongoro District was a mere stopgap because human behaviour would change and be hostile to the survival of wildlife.

However, at that time given the historical enmity between the Maa and the Wairak, the colonial rulers knew the Maa could not be pushed any further to intermingle with their historical foes.

The bromance between the colonial rulers and the Maa was in a mutual understanding that the latter’s way of life was not in conflict with wildlife it exemplified a symbiotic association that was of mutual benefit between wildlife and the Maa. The Maa did not hunt wildlife except for manliness validation of killing a lion, a ritual that was fading to extinction, so it was not a serious threat to wildlife coexistence with the Maa.

The Maa were not cultivators at that time so the conflicts of farming and wildlife were not a matter of concern until much later, when livestock populations were dwindling as a result of reduced precipitation, pestilence and cattle rustling. A combination of those factors left Maa with less livestock to feed themselves and cultivation was illegally introduced.

The government loudly sanctioned the illegal lifting of cultivation, during the Premier John Malecela who visited the area in 1992, and temporarily lifted it. Strangely, the lifting of the cultivation ban was not accompanied by the revocation of the cultivation ban statute, altogether.

According to Hon. Malecela, that decision was made purely for humanitarian reasons to afford the Maa and the authorities sufficient time to replenish the lost livestock populations. The estimated period to populate livestock was three years which ended in 1996. After the projected time had elapsed, it coincided with the Danida project that set aside funds to buy calves from nearby areas that would cope with Ngorongoro’s cold weather and leafy yet nutritious vegetation. The project was unsuccessful because of corruption and overlooking the contribution of the Maa in sustaining the project objectives just did it in.

Read Related: Is It Time to Retire Danish Aid to Tanzania After 60 Years?

Other associated projects were also crucial in the restoration of livestock populations in Ngorongoro. Infrastructural input in areas of earth dams, dips and livestock troughs were hastily constructed. The project objective was to reduce travel times in search of water, and grazing areas, and reduce ticks to lower livestock diseases. All these efforts were designed over a long time to populate livestock and persuade Maa to forsake cultivation and reinstate their traditional mode of life. Regrettably, it did not work!

Killer Assumptions Blew up The Danida Initiative

The Danida project was ambitious but had many serious flaws. First, it erroneously assumed that the newly formed pastoralist Council would replace the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority. The idealism behind this was that the Maasai (Maa) residents were in a better position to make decisions than the non-Maasai who were running the show.

This was a constitutional aberration of ethnic or tribal discrimination. Since Tanzania is a unitary government, any form of discrimination based on tribe or ethnicity is strictly prohibited. Thus, the Danida project was fundamentally flawed despite its substantial funding.

Paradoxically, the idea of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority being run solely by the Maasai was previously suggested by the first conservator of Ngorongoro, Henry Foosbroke (now deceased), during the recruitment of a conservator in 1987.

Foosbroke resigned from the Board of Directors of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority, citing that the appointment of non-Maasai was detrimental to the area’s survival. The then Minister for Natural Resources, Hon. Marcel Komanya (1989-1990), accepted his resignation and appointed a non-Maasai as the third conservator after Ole Saibul. Successors, including Hon. Abubakar Mgumia (1991-1993), followed this precedent.

The second critical assumption that has never been truly interrogated is who are the real Maasai? Inter-marriages, illegal in-migration, and civil servants and traders who settled there began identifying themselves as Maasai. Donning traditional Maasai attire or mastering the vernacular does not make one a Maasai deserving of all the associated rights and privileges.

Over the years, these factors inflated the Maasai population to a level that threatened wildlife survival. The Danida project made a genuine effort to identify the real Maasai, but government-supervised projects involved traditional leaders (Laigwanani), civil servants, and elected local leaders who legitimized many illegal immigrants.

Some of these explanations are difficult to contend with, particularly intermarriages and their interpretation based on Maasai traditions where principles of assimilation take precedence. Newcomers brought new tastes reflected in modern buildings, hired labor from Karatu and Mto wa Mbu to cultivate their farms, and used tractors to expand their arable lands. Potatoes from Nainokanoka were sold to tourist hotels like Ngorongoro Sopa Lodge, generating valuable cash.

Estimates indicated that Ngorongoro’s population would exceed 100,000 by 2040 as people flocked to the area, creating a welfare society that provided food, schooling up to university level, scholarships, water, livestock dipping, and security against cattle rustlers. The Danida project ended in 2006, but its mission continued, leaving a trail of issues. As Ngorongoro continued to provide benefits, illegal in-migration surged, prompting authorities to act.

The Ngorongoro Conservation Area general management plan, approved in 1996, was flawed from the start because it did not include human, livestock, and wildlife carrying capacities. Limits to human populations and their activities were not specified. For example, while the plan included building codes, the existence of permanent structures like hotels, schools, offices, and staff buildings eroded the moral authority to impose stricter building guidelines for Maasai residents.

Consequently, concrete and burnt brick structures replaced traditional thatched huts coated with cow dung, making the area an eyesore and intrusive to wild animals.

Solutions Were Never Apt!

For unclear reasons, the authorities decided to relocate the Maasai from Ngorongoro to Msomera village in Handeni district, Tanga region. A troubling question remains: why wasn’t the Ololosokwan area, which is large enough to accommodate most of the evacuated families and is within the Loliondo district, considered for resettlement?

The Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority has been farming in Ololosokwan for almost two decades, making it suitable for cultivation and permanent settlement. The benefits from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority could have been redirected there, reducing the complaints and anger associated with forceful evictions.

Additionally, the process of identifying the true Maasai residents was not conducted with integrity, leading to non-Maasai individuals receiving benefits they didn’t deserve. It seems there was political pressure to include everyone present, regardless of their legal residency status.

Long-term solutions for Ngorongoro’s issues should focus on exploring opportunities within the district before looking elsewhere. The main problems are overpopulation and human activities that harm wildlife management. Understanding these issues fully makes it easier to address them.

It is important to note that many families settled in the Northern Highlands Forests Reserves (NHFR) are not even Maasai. Since 2003, satellite maps have recorded over 200 families living there, cultivating land, harvesting trees for commercial purposes, and hunting. Removing these families is more urgent than evicting the Maasai, who pose less of an environmental threat.

Similarly, in the Engaruka area near Monduli, squatters have claimed large tracts of land, and past efforts to remove them met with strong resistance, risking violence and property damage. This issue was ignored by the former Minister for Lands and Settlements, Hon. Edward Lowassa, to appease his voters in Monduli constituency. If Ngorongoro boundaries are not respected, the area’s famous status is at risk.

Addressing land issues, as shown here, highlights the need to separate the roles of MPs and ministers, as they are often too compromised to provide sound leadership.

We must question why government priorities seem misplaced. Is there an underlying reason for the Maasai evictions while more harmful forest trespassers are ignored? “Whose priorities are these?” is a critical question that needs an honest answer for the betterment of all.