The decision by the Tanzania Revenue Authority (TRA) to impose a 5% tax on social media influencers and digital entrepreneurs has stirred strong debate. On the one hand, it reflects a legitimate push by government to expand its tax base in line with shifts in the economy. On the other, it raises critical questions about whether we truly understand and value the role young people play in shaping the country’s digital future.

For many young Tanzanians, platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube are not just entertainment outlets; they are pathways to income, opportunity, and self-expression. The so-called “creator economy” is not a fad. Globally, it is worth more than $100 billion and growing, with over 200 million people identifying as creators. With just a smartphone, internet access, and talent, young people can build businesses that employ editors, videographers, marketers, and software developers.

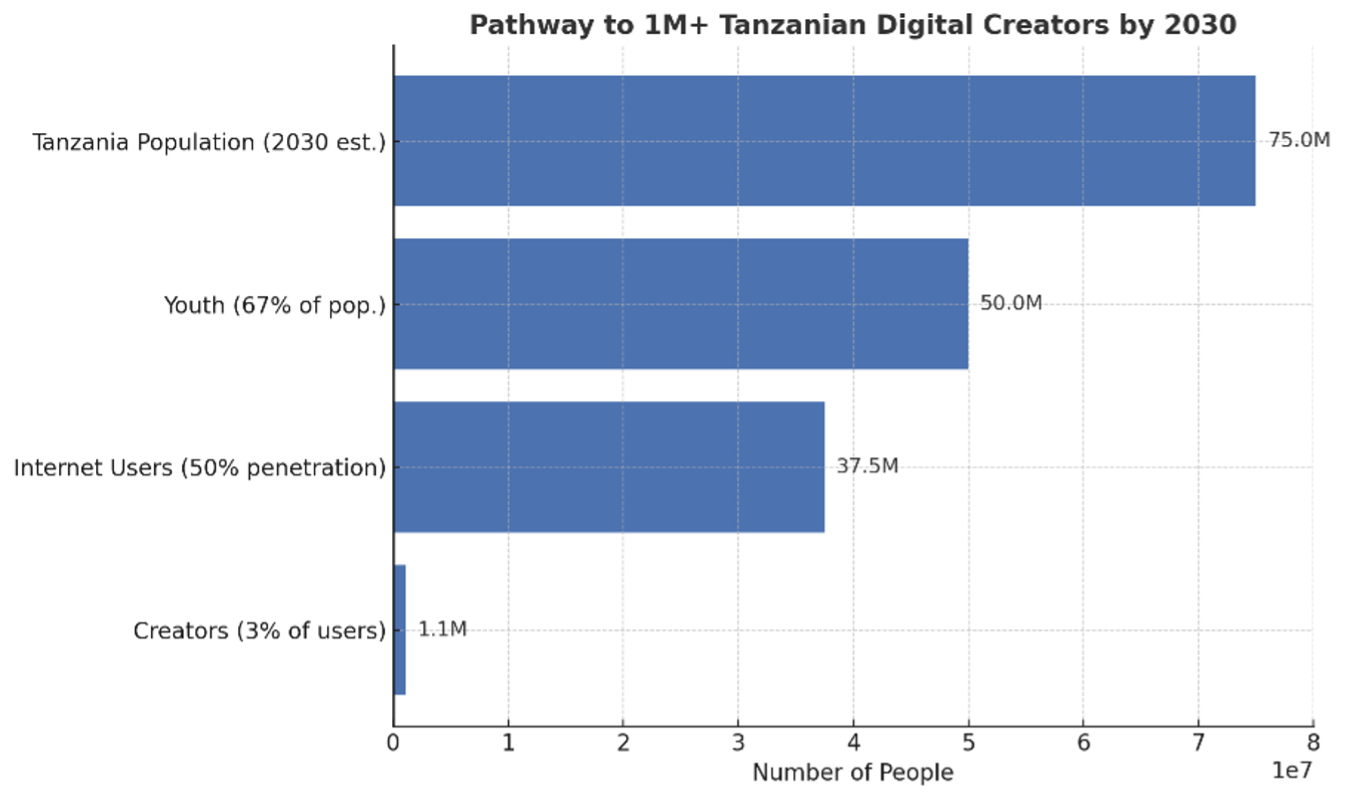

If nurtured, Tanzania could see over one million active digital creators by 2030, generating thousands of new jobs and billions of shillings in economic activity. We already have clear models to learn from. Nigeria transformed its cultural industries into global exports through Afrobeats and Nollywood. South Africa leveraged music, gaming, and digital media, especially Amapiano, to carve out global influence. These examples show how digital creativity, supported by enabling policy, can deliver both soft power and hard economic gains.

Yet the fragility of Tanzania’s digital ecosystem cannot be ignored. Despite 81% broadband coverage, only 26% of the population uses mobile internet regularly, largely due to the high cost of devices and data. Past policy experiments, such as mobile money levies, revealed how quickly poor design can backfire; usage dropped by nearly 40% when costs rose. Many young creators remain outside the formal economy because they fear taxation more than they see opportunity. A blanket tax risks reinforcing this cycle of informality.

This does not mean digital creators should not be taxed. It means they should be taxed differently. A youth-inclusive approach would start with progressive thresholds that exempt small earners while ensuring higher earners contribute fairly. It would include reinvestment of tax revenues into digital skills programmes, innovation hubs, and affordable device schemes. It would also prioritise simplified, platform-integrated compliance tools to reduce friction. Most importantly, it would create a mechanism for structured youth consultation, recognising young creators as partners in policy, not passive subjects of it.

The government is right to seek new revenue streams. But it is also responsible for cultivating the ecosystems that will drive growth for decades to come. Tanzania cannot afford to undermine its young digital innovators. If empowered, they have the potential to transform the country into a regional leader in digital culture and commerce. If overburdened, they risk retreating into informality, or worse, abandoning opportunities altogether.

The choice is clear: treat digital creators as targets for taxation, or as partners in building a resilient, inclusive economy. Tanzania’s future depends on the latter.