For most observers, a mine is defined by its pit and its ounces. But Nyanzaga’s real test will lie in systems that are less photogenic and more political: the power line that hums over villages, the pipeline that draws from Lake Victoria, and the dam that must hold billions of tonnes of waste for decades.

These are not back-office engineering details. They are the mine’s invisible foundations, and they will decide whether Nyanzaga is remembered as a model of responsible stewardship or a cautionary tale of risks deferred. Communities around Sengerema will not measure credibility in ounces but in whether their water stays clean, whether the lights flicker, and whether tailings stay contained.

Nyanzaga’s compact is therefore both environmental and economic. By choosing grid power over diesel, a zero-discharge tailings design over cheap embankments, and a monitored water intake over uncontrolled pumping, Perseus is not only building infrastructure but also signalling a political stance: that it understands Lake Victoria is not just geography, but a national symbol.

Power: the lifeline

Nyanzaga will draw its electricity from the national grid via a 53 km, 220 kV transmission line connecting to TANESCO’s substation at Bulyanhulu. This choice matters.

First, it means costs: grid tariffs are significantly cheaper than trucking in diesel for power generation. At ~US$0.10–0.12 per kWh, Nyanzaga’s power will be among the lowest-cost inputs in its budget. Second, it means carbon: grid electricity, dominated by natural gas and hydropower, cuts emissions compared to full diesel generation, aligning the project with ESG expectations.

But the choice carries dependencies. Tanzania’s grid is expanding, but it is not immune to outages. A line fault or hydro shortfall could cause the mill to idle. Perseus is mitigating the risk with backup diesel generation for critical circuits, but prolonged outages would still impact throughput.

For communities, the line is a symbol: pylons will stride across villages, visible proof of industrial progress. The political risk is exclusion. If the mine is electrified while surrounding villages remain dark, the infrastructure could become a grievance rather than a symbol of shared progress.

Water: Lake Victoria’s shadow

Water is the most sensitive resource in Sengerema. Nyanzaga will draw raw water from Lake Victoria, just a few kilometres north of the mine. For the plant to treat 5 Mtpa of ore, it will require steady volumes of make-up water, particularly in dry seasons.

On paper, the draw is small relative to the lake’s scale, a few hundred cubic metres per hour from a water body holding thousands of cubic kilometres. But perception is as essential as hydrology. Lake Victoria sustains millions of people: fishing livelihoods, domestic water use, and regional ecosystems. Any suggestion that mining threatens this lifeline risks immediate backlash.

Perseus’s commitment is a zero-discharge water balance. All process water will be recycled from the tailings facility; lake water is only for make-up. Monitoring wells and community reporting are planned to provide reassurance to stakeholders. Even so, memories of past pollution incidents elsewhere in the Lake Zone linger.

Politically, the pipeline is both an asset and a liability. It anchors the mine’s viability but also binds it to the fate of the lake. Success will mean water use so invisible it draws no comment; failure would mean Nyanzaga is remembered less for its ounces than for a scar on Africa’s most excellent inland sea.

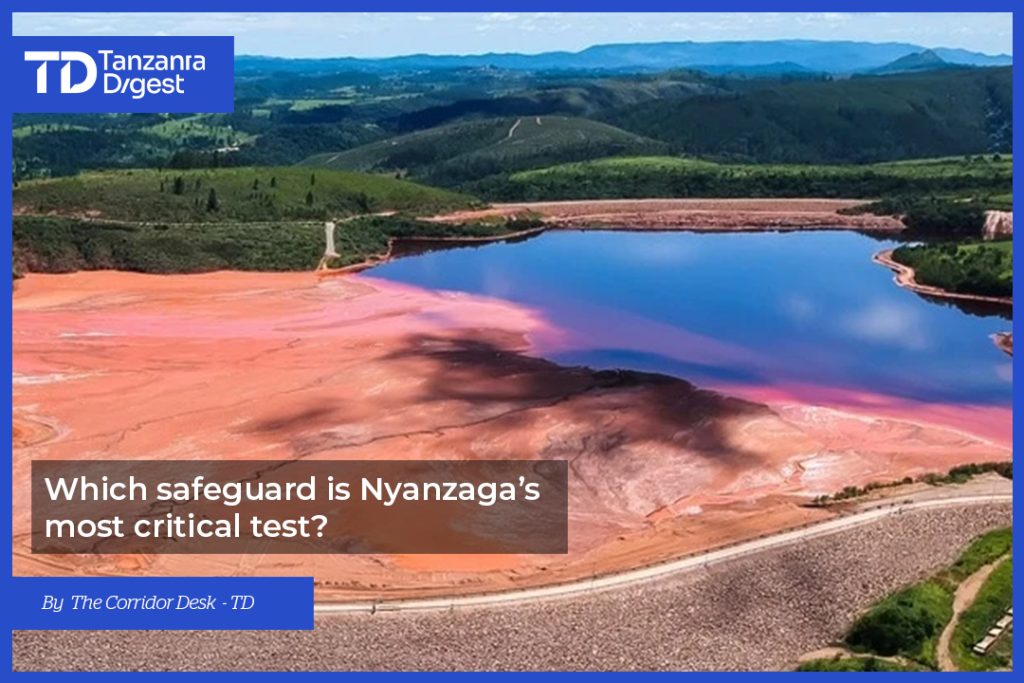

Tailings: the actual test

If water is sensitive and politically powerful, tailings are existential. Nyanzaga’s processing plant will generate millions of tonnes of finely ground waste material, which must be stored safely for the life of the mine and beyond.

The design is ambitious: a downstream-built, lined Tailings Storage Facility (TSF) engineered to international standards (ICOLD/ANCOLD). Embankments will be zoned as earthfill, lined with clay and HDPE, and equipped with underdrainage to capture seepage. A central decant barge will recycle water back to the plant. Independent reviewers will oversee design and operation.

These features matter because tailings failures elsewhere have destroyed reputations and communities. In the Lake Victoria basin, the stakes are even higher. A single breach could devastate fisheries, villages, and Tanzania’s mining credibility.

For Perseus, the TSF is more than engineering; it is politics in soil and stone. A well-run facility will reassure regulators, attract ESG-conscious investors, and lend legitimacy to the project. A failure, however minor, would overshadow every other achievement. For villagers farming beneath the embankments, trust will not come from design reports but from years of safe, uneventful operation.

Integrated safeguards

Nyanzaga’s designers know that power lines, pipelines, and dams alone do not guarantee safety. The project’s credibility rests on the systems layered around it.

- Cyanide management: a detox circuit ensures residual cyanide in tailings is broken down before deposition, with targets aligned to the International Cyanide Management Code.

- Mercury and arsenic: scrubbers and precipitation units capture these elements, preventing their release into the atmosphere and locking contaminants into stable forms.

- Stormwater management: diversion channels steer clean rainwater around the site; emergency ponds capture runoff during heavy rains, ensuring nothing uncontrolled flows toward Lake Victoria.

- Monitoring systems: water quality sensors, piezometers in the dam walls, and SCADA-linked power line monitors create a continuous flow of data.

These safeguards are not cheap, but they are politically essential. In Tanzania’s current climate, one uncontrolled discharge could cost more than any upfront investment in prevention. For Perseus, they are less about compliance than about protecting the very legitimacy of the mine.

Community perspective

Infrastructure looks different from a village courtyard. For investors, a 220 kV line is a cost item; for a farmer, it is a symbol of electricity that passes overhead without ever lighting their home. For regulators, a water pipeline is a technical solution; for a fisher on Lake Victoria, it is a potential threat to their catch and livelihood. For engineers, a tailings dam is designed in cubic metres of storage; for villagers downstream, it is a looming wall of risk.

This gap in perception is critical. Communities judge infrastructure not by design reports but by lived experience. Will the power line bring off-grid connections to schools? Will the pipeline deliver boreholes or improved access to clean water? Will the TSF embankments stand silent for decades without leaks or scares?

Trust, therefore, depends on transparency and reciprocity. Publishing water monitoring results, inviting local observers to tailings inspections, and visibly sharing the benefits of infrastructure can turn suspicion into ownership. Failing to do so risks leaving infrastructure as symbols of exclusion.

Risks and opportunities

Nyanzaga’s environmental compact is a ledger of risks and opportunities.

Risks:

- Grid dependence: power outages or tariff hikes could disrupt production and raise costs.

- Water stress: although Lake Victoria is vast, seasonal droughts or localised impacts could trigger alarm.

- Tailings vulnerability: Extreme rainfall events, which are increasingly frequent due to climate change, could test dam resilience.

- NGO scrutiny: environmental groups will track every incident, amplifying minor failures into national controversies.

Opportunities:

- Renewables: supplementing the grid with solar-diesel hybrids could cut emissions and costs.

- Shared infrastructure: extending spur lines or boreholes from mine systems to nearby villages could transform community relations.

- Global ESG capital: strong environmental performance can attract sustainability-focused investors, lowering the cost of capital for Perseus.

- Policy credibility: for Tanzania, a safe Nyanzaga strengthens the argument that mining reforms deliver not just fiscal revenue but environmental integrity.

The balance is delicate. A single misstep could outweigh years of careful planning; conversely, a record of safe and transparent operations could make Nyanzaga a regional model.

Infrastructure as legitimacy

When future Tanzanians look back at Nyanzaga, they may not remember the strip ratio or the ore grade. They will remember whether the power stayed on, the lake stayed clean, and the dam stayed safe.

Infrastructure at Nyanzaga is thus more than engineering. It is legitimacy made concrete. The transmission line anchors the mine into the national economy; the water pipeline binds it to Lake Victoria; the tailings dam tests its environmental responsibility daily. Each is a physical expression of the compact between Perseus, the Tanzanian state, and the people of Sengerema. If these systems run safely and visibly deliver benefits, Nyanzaga will stand as proof that large-scale mining can coexist with East Africa’s most precious freshwater basin. If they falter, the failures will eclipse the ounces, leaving the mine remembered less for wealth created than for risks imposed.