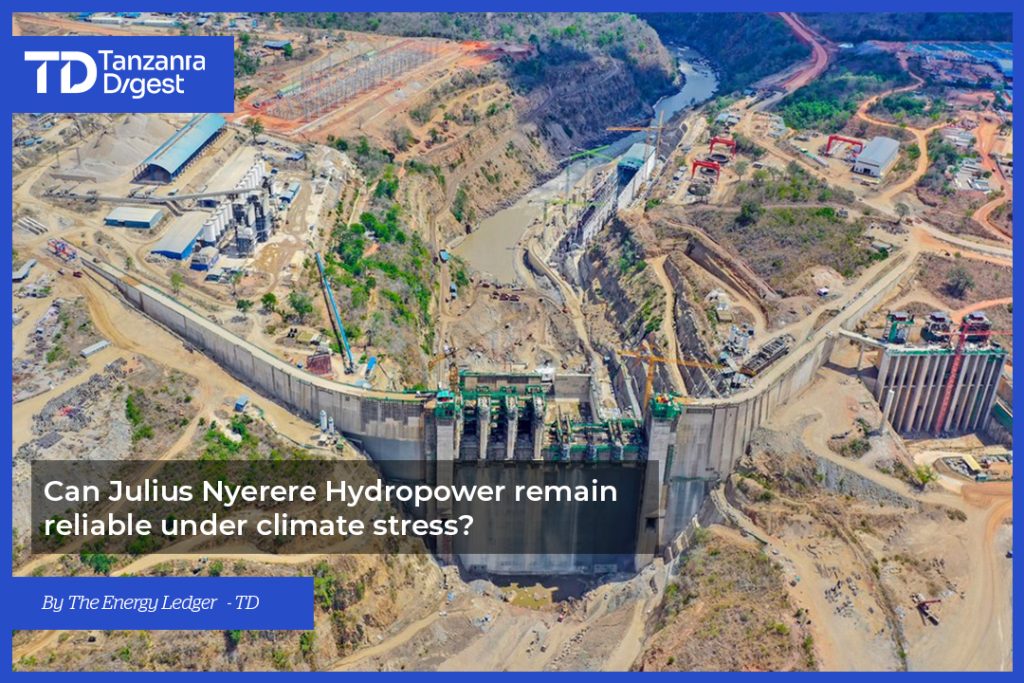

From the air, the Julius Nyerere Hydropower Plant looks like a symbol of permanence: 2,115 megawatts of generating capacity, a vast concrete wall holding back billions of cubic meters of water, and a reservoir that stretches far into the Selous landscape. Yet the reality is more fragile.

Hydropower, for all its engineering strength, depends entirely on something that cannot be engineered: the steady flow of water. If the river runs low, turbines fall silent. And as climate patterns shift, the risk of reduced inflows is no longer a distant possibility; it is a planning reality.

Tanzania has invested heavily in JNHP as the backbone of its power system, but that backbone is tied to the climate. The question now is whether we are building an energy strategy that can withstand both the dry and wet years.

Hydropower’s Climate Vulnerability: Lessons from Elsewhere

Hydropower plants are built with decades of service in mind, but their actual output can vary dramatically from year to year depending on rainfall. Installed capacity is a promise on paper; actual generation is the reality on the ground.

We need only look elsewhere in Africa to see the risks. Zambia’s Kariba Dam, once a symbol of regional power and security, has faced repeated generation cuts due to drought. In 2015, 2019, and again during the 2022–24 period, low lake levels forced output reductions so severe that only one of six turbines was operational at times, leading to widespread blackouts and an immediate drag on GDP.

Ghana’s Akosombo Dam has seen similar episodes. In 2007, drought reduced its output from about 1,180 MW to just 400 MW, triggering nationwide power rationing and pushing up the cost of alternative generation.

These cases highlight the harsh reality: regardless of how modern the turbines are, hydropower output is only as dependable as the water supply feeding it. For Tanzania, the question is whether JNHP will encounter similar challenges in the coming decades and how we can prepare for them.

The Rufiji River Context Variability Built In

The Rufiji River is Tanzania’s largest, with a basin that supports agriculture, fisheries, and now the country’s most ambitious power project. Historically, its flows have followed seasonal patterns — high volumes during the rainy seasons and reduced flow in the dry months.

Climate projections for East Africa suggest a future of greater variability rather than a simple increase or decrease in rainfall. More intense downpours may occur, but so will longer dry spells. This kind of pattern is particularly challenging for hydropower, which needs steady inflows to maintain output.

There are also non-climatic pressures. Upstream land-use changes, deforestation, and irrigation expansion can alter runoff patterns and decrease inflows. Without careful basin management, these factors can increase the risk of low water levels even in years that are not technically “drought years.”

For JNHP, this means the vulnerability is twofold: climate-driven variability that changes the timing and amount of water, and human-driven changes upstream that could steadily erode the dam’s dependable supply. Both must be factored into the financial and operational planning if Tanzania wants to safeguard this enormous investment.

Economic Stakes for Tanzania

When a single plant provides such a large share of the nation’s generation capacity, its vulnerability becomes the country’s vulnerability. JNHP is designed to be the backbone of Tanzania’s electricity mix, feeding industries, powering exports, and stabilizing tariffs. But over-dependence on one hydrological source magnifies risk.

A sustained drop in Rufiji River inflows could trigger:

- Industrial productivity losses from power cuts disrupt manufacturing output and erode export competitiveness.

- Tariff pressure, as lower hydropower output forces reliance on more expensive diesel or gas-fired generation.

- Revenue instability in cross-border energy trade, as Tanzania could be unable to fulfill power export contracts reliably during drought years.

We have already seen this play out elsewhere. Kariba’s low water years have cost Zambia hundreds of millions in GDP losses, while Ghana’s Akosombo shortages have forced emergency power procurement at high cost. In both cases, the financial impact was not limited to utilities; it rippled through the economy, increasing business costs and slowing growth.

For Tanzania, the lesson is simple: climate volatility equals revenue volatility. If JNHP is the anchor of our power system, we must ensure the anchor doesn’t drag during a storm.

Risk Mitigation Strategies

Diversify the Energy Mix

Treat JNHP as a backbone, not a monopoly. Expanding solar, wind, and geothermal generation can hedge against hydrological risk. These resources can complement hydro seasonally, filling in supply gaps during dry spells.

Integrated Basin Management

Upstream land-use practices directly affect river flow. Implementing sustainable forestry, regulating irrigation withdrawals, and protecting watershed areas can stabilize inflows. The Rufiji Basin should be managed as both an energy asset and an ecological resource.

Climate-Responsive Operations

Adopt reservoir management policies that incorporate seasonal forecasts and climate models. Carryover storage strategies, which involve maintaining higher reserves during wet years, can help smooth generation through multi-year droughts.

Industrial Contingency Planning

Work with major power users to prepare priority load plans and alternative generation strategies for low-flow periods. This reduces the economic shock of sudden rationing.

Governance and Planning

Mitigating climate risk at JNHP is not only a technical task; it is a governance challenge. It requires coordination among ministries, utilities, regulators, and regional partners.

- Integrate Climate Scenarios into Energy Policy: The Power System Master Plan should include stress tests for multi-year drought conditions and adjust investment priorities accordingly.

- Transparent Risk Reporting: TANESCO and the Ministry of Energy should publish annual hydrology and climate risk assessments for JNHP, including reservoir levels and inflow trends.

- Cross-Border Coordination: Since JNHP may feed regional grids, climate risk planning must be part of Tanzania’s energy diplomacy, ensuring trading partners understand both capacity and constraints.

- Funding for Adaptation: Leverage climate finance mechanisms to fund resilience measures from watershed conservation to solar and wind integration.

Planning for the Dry Years

The Julius Nyerere Hydropower Plant is a remarkable engineering achievement and a critical part of Tanzania’s growth story. But no matter how strong the concrete or modern the turbines, their output will always be limited by the water that flows into the Rufiji River.

We cannot control the climate, but we can control our preparedness. That means diversifying our generation mix, protecting watersheds, adapting operational policies, and integrating climate risk into every level of planning.

The cost of doing so is far less than the economic price of a drought-induced power crisis. The time to act is before the first major dry year tests the system, not in the middle of it. In the long term, JNHP will be judged not just by the power it produces in good years, but by how well it keeps the lights and the economy on when the river runs low.