There are myths about “Tanzania Nakupenda Kwa Moyo Wote” that remain intriguing today as they were pre-1964 days. Many believe it is a Chinese song that has been localized with few lyrics retouched. But was it?

The folklore argues that first president Julius Kambarage Nyerere during his maiden visit to China heard the song, and was impressed. He asked the Chinese authorities to reconfigure it in Kiswahili and teach Tanzanians how to sing it. Is there any truth in it?

This narrative fits with how our national anthem was picked. Our national anthem is a South African import. Therefore, it attracts considerations that even “Tanzania Nakupenda Kwa Moyo Wote” was a foreign adopted.

This article may not clear the air but attempts to chronicle sources of both songs beginning with the national song and “Tanzania Nakupenda Kwa Moyo Wote”. Here are my thoughts which stand to be corrected. Let’s go.

Mungu Ibariki Afrika: From ANC Liberation Hymn to Tanzanian Anthem.

Origins and Adoption of Tanzania’s National Anthem

Tanzania’s national anthem, “Mungu ibariki Afrika” (God Bless Africa), originated from the South African hymn “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (Lord Bless Africa), composed in 1897 by “Enoch Sontonga”, a Xhosa Methodist teacher. Here’s how Tanzania obtained and adapted it.

Liberation Roots, National Voice: Tanzania’s Adaptation of ‘Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika’.

Key Historical Steps.

South African Roots and Liberation Symbolism.

Sontonga’s hymn was initially a church song but gained prominence as the “official anthem of the African National Congress (ANC)” in 1925.

During apartheid, it became a “pan-African liberation anthem”, symbolizing resistance against colonialism and racial oppression. Its melody spread across Africa through anti-colonial networks.

Adoption by Tanganyika (1961).

When Tanganyika (mainland Tanzania) gained independence from Britain in 1961, it replaced “God Save the Queen” with a “Swahili adaptation” of “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika“.

The translation was led by “Julius Nyerere”, Tanzania’s first president, who refined the lyrics to emphasize “unity, peace, and post-independence aspirations”. The anthem was officially titled “Mungu ibariki Afrika“.

Post-Union Adoption (1964).

After Tanganyika united with Zanzibar in 1964 to form Tanzania, the anthem was retained, replacing Zanzibar’s existing anthem.

Localization and Cultural Significance.

Lyrical Adaptation: While the melody remained identical to Sontonga’s original, the Swahili lyrics were “customized for Tanzanian context”. For example:

Original Xhosa: Focused on blessing Africa broadly.

Swahili version: Added specific references to Tanzania, leaders, and unity (e.g., “Dumisha uhuru na Umoja” – “Preserve freedom and unity”).

Nyerere’s translation intentionally used “religiously neutral language” (e.g., “Mungu” for God) to bridge Christian and Muslim communities.

Symbol of National Identity: The anthem became a “tool for nation-building”, sung daily in schools to instill patriotism. It reflects Tanzania’s “linguistic unity”, as Swahili (spoken by 90%+ of the population) replaced tribal languages.

ANC Liberation Song or Locally Inspired?

Liberation Heritage: The anthem is “undeniably rooted in the ANC struggle”, sharing its melody with liberation movements across southern Africa (e.g., Zambia, Zimbabwe).

Local Reinterpretation: However, Tanzania “transformed it into a distinct national symbol”: Lyrics centered on “Tanzanian sovereignty”, not pan-African liberation. Integrated into “local traditions”, like “ngoma” (drumming) performances and state ceremonies.

Myth-busting: Despite rumors that Nyerere imported it from China during a 1960s visit, historical records confirm its direct link to Sontonga’s hymn.

Broader Impact.

Pan-African Legacy: The melody is still shared with South Africa (combined with “Die Stem”) and Zambia.

Controversies: In 2007–2013, legal battles arose when Jehovah’s Witness students refused to sing it, citing religious objections. Courts ultimately ruled singing was optional.

Conclusion: Rooted in Resistance: How Tanzania Adopted a South African Freedom Song.

Tanzania’s anthem is a “fusion of South African liberation heritage and localized nation-building”. While its melody is a tribute to anti-colonial solidarity, its Swahili lyrics and daily use reflect Tanzania’s unique journey toward unity and cultural identity. As one of Africa’s earliest adopters of “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” Tanzania cemented the hymn’s status as a “continental symbol of freedom”.

Fun fact:

The anthem’s composer, Enoch Sontonga, was honored with a Google Doodle on South Africa’s Freedom Day (2017) for his unifying legacy.

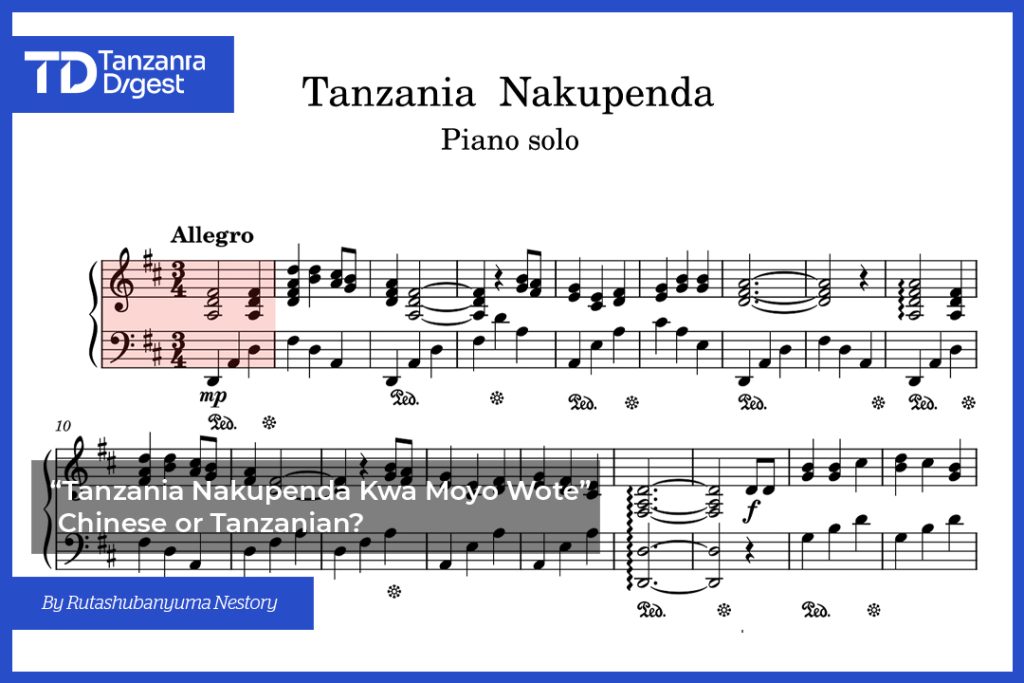

Unraveling the Origins of ‘Tanzania Nakupenda.

“Tanzania Nakupenda Kwa Moyo Wote” is definitively a local Tanzanian song in Kiswahili, with no evidence of Chinese origins. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

Origin and Authorship.

The song emerged in Tanzania, with roots tracing back to the colonial era (pre-1964). It was initially titled “Tanganyika, Tanganyika nakupenda kwa moyo wote” and adapted to “Tanzania” after the union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar in 1964.

Its authorship remains uncertain, but it is widely attributed to Tanzanian or East African creators, possibly developed as part of early national identity efforts during the transition from British colonial rule.

Lyrics and Cultural Context.

The lyrics express deep patriotism for Tanzania, referencing its landscapes, people, and role as a refuge for those facing hardship (e.g., “Karibu wasio na kwao / Wenye shida na taabu” – “Welcome those without homes / Those with troubles and misery”).

Translations confirm the content is exclusively Tanzanian-centric, with no linguistic or thematic ties to Chinese culture.

Musical Use and Significance.

The song is frequently performed alongside Tanzania’s national anthem (“Mungu Ibariki Afrika“) at official events, schools, and public gatherings.

Examples include:

A 2015 performance for former President Jakaya Kikwete in Australia.

Rural school renditions (e.g., Maboha Primary School).

Recordings by Tanzanian choirs like La Mennais Choir Moshi.

No Chinese Links.

“No evidence” in any source suggests Chinese origins. The tune, lyrics, and historical context are consistently tied to Tanzania.

While some national anthems or patriotic songs globally share musical influences (e.g., African liberation movements), this song’s structure and melody align with local Swahili traditions rather than foreign adaptations.

A Song’s Dual Narrative: National Pride and Diplomatic Folklore.

“Tanzania Nakupenda Kwa Moyo Wote” is a purely Tanzanian creation reflecting national pride and post-independence identity. It is “not a translated Chinese song”, and Tanzania adopted neither its lyrics nor tune from external sources. Its enduring popularity underscores its role as a cultural emblem.

China Not Authored It?

Nyerere, China, and the Making of a Tanzanian Anthem.

The widespread belief in Tanzania that Julius Nyerere brought the patriotic song “Tanzania, Tanzania Nakupenda Kwa Moyo Wote” back from China stems from a confluence of historical, cultural, and political factors, despite “no evidence” supporting this origin myth. Here’s a breakdown of why this narrative persists, based on the search results and historical context:

Nyerere’s Documented Engagement with China.

Nyerere maintained “strong ties with China” post-independence, viewing it as a fellow anti-colonial and socialist ally. His visits to China (e.g., in the 1960s–70s) were highly publicized, emphasizing “ideological exchanges” and infrastructure projects like the TAZARA Railway.

During these visits, “cultural performances” were integral to diplomacy. For instance, Chinese choirs performed Tanzanian folk music for visiting leaders like President Kikwete in 2014, showcasing mutual artistic appreciation. This precedent fuels speculation that similar exchanges occurred during Nyerere’s era.

] Symbolic Alignment of Ideologies.

Nyerere’s “Ujamaa socialism” (rooted in communal African values and Catholic social teaching) paralleled aspects of Chinese socialist rhetoric, creating a perceived “cultural affinity”.

Tanzanians witnessing Chinese revolutionary songs might have “projected similarities” onto their own patriotic hymns. The song’s emphasis on national unity and sacrifice resonated with both Ujamaa and Maoist collectivism, making a Chinese influence seem plausible.

Nation-Building and the “Father of the Nation” Aura.

Nyerere was revered as “Baba wa Taifa” (Father of the Nation). Stories attributing national symbols to his personal actions, like “discovering” a song abroad, reinforce his “mythic role” in crafting Tanzanian identity.

The song’s ubiquity in schools and state events since the 1960s created a vacuum of origin stories. Linking it to Nyerere’s diplomacy provided a “foundational narrative” fitting his image as a visionary leader.

Post-Colonial Cultural Synthesis.

Tanzania’s nation-building involved “curating a hybrid culture”. Adopting foreign elements (e.g., translating Nyerere’s works into Chinese) was common. Rumors of a Chinese tune being “localized” into Swahili align with this ethos of “adaptive patriotism”.

The absence of formal authorship for the song (as with many oral traditions) left room for “oral histories” to fill the gap, especially given Nyerere’s admiration for China’s discipline and cultural organization.

Why the Narrative Endures Despite Evidence.

“No credible sources” link the song to China. Its lyrics and structure align with Swahili poetic traditions and post-independence East African hymns.

The persistence of this myth reflects “deeper truths”:

Tanzanians’ pride in Nyerere’s internationalism.

The song’s emotional power as a “unifying artifact”, enhanced by exoticizing its origins.

Post-Cold War reinterpretations of Tanzania’s socialist era, where China symbolized a “model” for development.

A Song’s Dual Narrative: National Pride and Diplomatic Folklore.

While the song is “unambiguously Tanzanian”, the myth of its Chinese origins persists as a “cultural metaphor” for Nyerere’s diplomatic legacy and Tanzania’s openness to global solidarity. It underscores how national memory intertwines fact and folklore to celebrate leaders who shaped identity. For deeper insight, explore Nyerere’s speeches in “Selected Works” or analyses of Ujamaa’s cultural impact.